Deconstructing Borders: Capturing Sights and Sounds from La Frontera

The border, or la frontera, between the United States and Mexico lies along a severe, natural landscape that is both beautiful and dangerous. Tracing the contours of the Rio Grande for much of its length, it is a place fraught with social, political and cultural tensions—a space where mystery and tragedy coexist, where beauty and horror lay side-by-side.

For noted photographer Richard Misrach and composer Guillermo Galindo, co-creators of Border Cantos |Sonic Border, an exhibition showing at the Hudson River Museum through May 9, the ineffable qualities of the land and its soundscapes first led them to collaborate in 2012. The controversial wall, stretching 1,954 miles from Brownsville, Texas to San Diego, California, and its impact on people and communities, brought the artists together to explore themes of light, sonority and migration.

Working with natural materials, found objects, and artifacts collected from the region’s vast expanse, each artist brings distinct perspectives to the project. Through images, textures and sonic elements, shared aesthetic sensibilities coalesce to articulate a unified creative “voice.”

Laura Vookles, the museum’s chief curator, describes this artistic synergy: “Each can be appreciated for its own merits and message, but to stand in the space, surrounded by these monumental photographs of the Border, listening to music that evokes the sounds of being in the desert near the wall, resonates on another level. We sense, as much as see and understand, what the human story of this landscape is and what the landscape is of this human story.”

The interplay of natural and human elements are linked by the brutality of the wall and its impact on people and communities on both sides. In a sense, the wall connects the conceptual to creative expression, serving as a central theme and structural backbone of the exhibition.

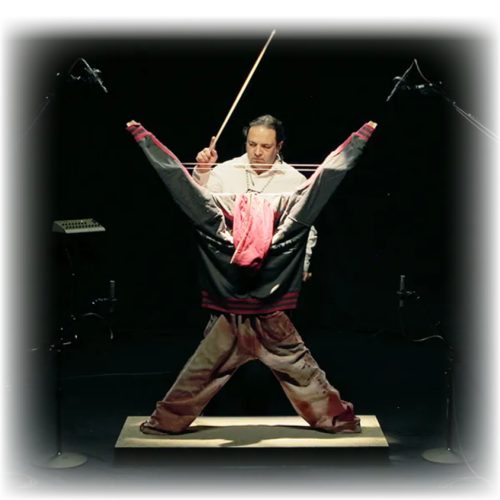

The unique, hybrid musical instruments that Galindo builds for experimental compositions make reference to indigenous, pre-Columbian, Meso-American and world cultures. His recorded score for eight instruments loops intermittently, creating a sonic counterpoint to Misrach’s large format photography. This juxtaposition invites visitors to enter and experience spaces that, although ephemeral and absent of people, are nonetheless filled with life—and death. The desert feels palpable, alive and balanced. Although most people will never go there, the works here provide a glimpse of hard-edged realities and challenges that border-crossing migrants face. Audiences are subtly encouraged to think about the artificial nature of constructed barriers that are set in natural environments, and to consider the cultural divisiveness that results between “civilized” societies.

Galindo’s musical instruments are placed in the center of the gallery, surrounded by Misrach’s photographs. In a “concert” of desert timbres, tones and silences, the music conjures a shamanic ritual that echoes throughout the museum.

While the absence of people is explicit, in one photograph a human form appears obscured behind a steel curtain, outlining the shape of a young woman—essentially a shadow figure. The effect of this ghost-like silhouette suggests anonymity and the dehumanizing effects of border walls, the denial of a migrant’s dreams and the destructive impact on communities for both sides of la frontera.

The inherent energy in human objects, from a child’s teddy bear and discarded clothing to playing cards and CDs, from bone fragments and shell casings to Pedialyte bottles and more, all become totemic remnants of a nameless archeology, the detritus of human migration.

Misrach’s Effigy 2 depicts three constructed figures standing before a passageway and overpass. Are they markers of a safe passage, or a warning? Whomever created and placed them, and what purpose they were intended for, is unclear and ambiguous. Misrach’s image raises more questions than it answers. Using the same materials, Galindo’s Efigie attaches steel strings across the raised arms and chest of Misrach’s figure to create a musical instrument that gives “voice” to the migrant sculpture.

As young men, Misrach and Galindo were both inspired by the literature of Carlos Castaneda, whose narratives pointed to a spiritual cosmology of the desert and the many secrets contained in its mountains, rivers and wildlife. Border Cantos |Sonic Border similarly invokes this supernatural world, along with unknown lives and lived experiences of people in migration.

The intensity of this exhibition highlights what is artistically (and perhaps politically) possible when artists collaboratively create works that are simultaneously historical, representational and symbolic—artworks that cut across national, transnational, or “binational” borders and identities to express something utterly and totally human.

Jorge Arévalo Mateus, Ph.D., is an arts and culture educator and advocate. A musician, ethnomusicologist, and folklorist, he teaches in the Department of Race and Cultural Studies at BMCC-CUNY.

A version of this article first appeared in the April issue of ArtsNews, ArtsWestchester’s monthly publication. ArtsNews is distributed throughout Westchester County. A digital copy is also available at artsw.org/artsnews.