We Can Do It! Women’s Work at Lyndhurst

by Michelle Falkenstein

What does a 19th century memorial wreath made from human hair have in common with a wall hanging woven from synthetic hair extensions by contemporary artist Nafis White? Everything.

Women’s Work, an exhibition at Lyndhurst Mansion in Tarrytown, draws a thread from the domestic handiwork done by women from Colonial times onward—embroidery, painting on porcelain, black paper silhouettes, beadwork, quilting and more—up to the artists of today who have adopted these techniques.

The concept for the show, says Lyndhurst Executive Director Howard Zar, is not to demonstrate how these handicrafts have been elevated by their use in current art-making practices, but rather to show that they were art all along—the only kind that women, for centuries, were taught or allowed to make.

The 125 objects in the exhibition, displayed both in Lyndhurt’s gallery and throughout the Mansion, are grouped by technique, providing a clear connection between past and present. One such assemblage features a yellow and rust needlepoint seat cushion in a scallop pattern, made by First Lady Martha Washington (1801) and an embroidered silk pin cushion sewn by First Lady Dolley Madison (made by 1789). These items are displayed beside a sculpture of a human head roughly stitched together with scraps of tapestry by artist Louise Bourgeois (2002) and what, at first glance, appears to be a traditional sewing sampler by Elaine Reichek (1993). At closer look, it’s neatly embroidered with the words, “The Parents of Jewish Boys Always Love Me. I’m the Closest Thing to a Shiksa Without Being One.”

Says Zar: “A lot of people think they don’t like contemporary art. When they see it in this new way, they actually like it.”

He adds that there are lessons here for Millennials who may believe that things have always been done the way they are today. “We’re trying to show the long history of our culture,” he says.

Lyndhurst, a stately Gothic Revival mansion rising over the banks of the Hudson River in Tarrytown, has a strong connection to women. It was commissioned in 1838 with a woman’s fortune and was owned by more women than men before it was bequeathed to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1961. Zar says that because of this legacy, Lyndhurst “often do[es] shows about the impact of women on American cultural history.”

Featured prominently in the exhibition is a wax figure of a woman made in 1720 by Sarah Gardner. It’s one of only two 18th century wax figures in existence. The figure, standing under a glass dome, wears a mustard-yellow gown, her head surrounded by a halo of pears. Nearby stands Shary Boyle’s Curupira (2014), a mythological Brazilian creature with a distorted nude body, cast in porcelain, her feet pointed backward.

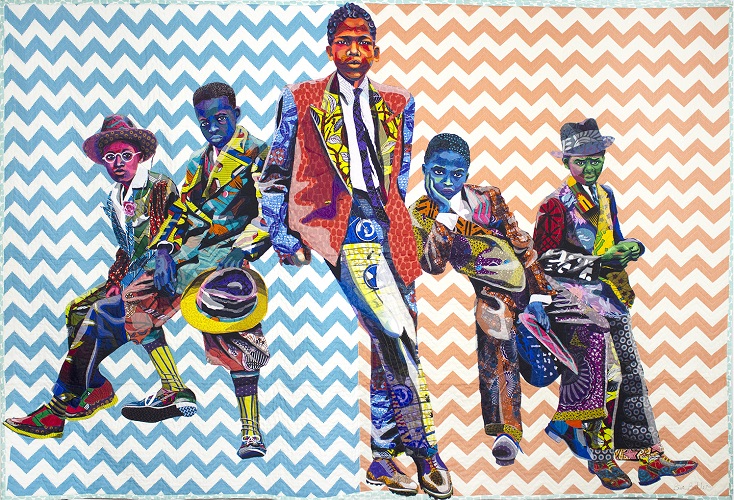

There are many well-known contemporary artists in the show, including Faith Ringgold, Kara Walker, Catherine Opie, Kiki Smith and Judy Chicago. And although many women toiled anonymously in centuries past, a real effort was made to choose pieces whose makers could be identified, such as Emily Cole (sister of Hudson River School artist Thomas Cole), Jane Armstrong Tucker and Susanna Jaquith Abbott.

“Regardless of the systematic injustice of a biased world,” Zar writes in the exhibition catalogue, “women artists working over centuries have found ways to validate their artistic identity.”

A version of this article first appeared in the July-August 2022 issue of ArtsNews, ArtsWestchester’s monthly publication. ArtsNews is distributed throughout Westchester County. A digital copy is also available at artsw.org/artsnews.

About Michelle Falkenstein

Michelle Falkenstein writes about culture, food and travel. Publications include The New York Times, Journal News, Albany Times Union, ARTnews Magazine and (201) Magazine